How Legal Frameworks Enabled Human Rights Violations During the July Uprising

- Publish : 10:11:32 am, Sunday, 10 August 2025

- / 49

file Photo

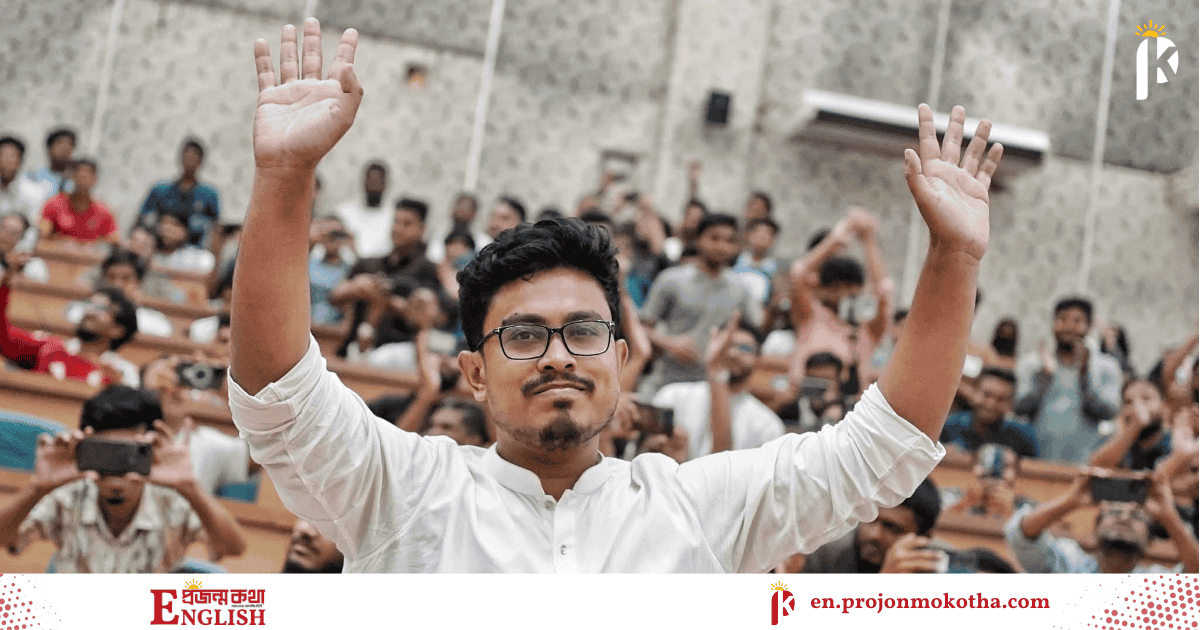

The July–August 2024 mass uprising, which began as a movement to reform Bangladesh’s unjust and discriminatory quota system in public employment, soon transformed into a nationwide call for equality and an end to systemic discrimination. Led by students and supported by people from all walks of life, the movement was met with unlawful attacks and brutal suppression by the then government’s law enforcement agencies.

According to a UN fact-finding mission, the indiscriminate and unlawful use of lethal weapons, coupled with unjustified “shoot-on-sight” orders, killed as many as 1,400 people including children and injured thousands more. The violent crackdown amounted to crimes against humanity, mass killings, and gross violations of fundamental rights.

During the uprising, thousands of student protesters were arbitrarily detained and subjected to torture, blatantly violating the constitutional guarantees of personal liberty and due process, as well as international human rights standards.

The government’s imposition of internet shutdowns further violated civil and political rights, particularly freedom of expression, access to information, and the right to peaceful assembly. In each case of violation, the law was either misused to justify state actions under the guise of “national security” and “public interest,” or was weaponised to enable oppression, harassment, and torture.

The uprising revealed how the law had long been manoeuvred to legitimise rights violations. Repressive legal instruments, notably the Digital Security Act (DSA) a successor to the notorious Section 57 of the ICT Act entrenched digital authoritarianism.

A Centre for Governance Studies report revealed that from October 2018 to January 2023, a staggering 7,001 cases were filed under the DSA against 21,867 individuals, including activists, journalists, students, and ordinary citizens. The law’s vague and overly broad provisions empowered law enforcement to detain individuals without warrants, block digital content, and silence dissent all without due process.

The deliberate crafting and selective application of such laws fostered a climate of fear, self-censorship, and intimidation, prioritising political interests over safeguarding digital rights.

Defamation provisions under colonial-era penal codes, the Contempt of Court Act, and the DSA were also weaponised to stifle criticism. Ruling party members routinely filed multiple defamation cases as aggrieved persons against journalists, editors, and activists a clear departure from the Code of Criminal Procedure, which allows only genuinely aggrieved individuals to file such cases.

Institutional failures further compounded the problem. The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) was legally barred from investigating violations by security forces, rendering it ineffective. Even eight months after the resignation of its chairman and members in November last year, no new commission has been formed. The interim government has yet to remove legal barriers, strengthen capacity, or ensure the NHRC’s independence.

Poor enforcement and selective application of the law created a culture of impunity for abusers, where the legal system functioned as a tool of oppression rather than protection. In a country already suffering from fragile rule of law, limited judicial independence, and democratic deficits, such misuse proved especially devastating.

The July uprising offered a unique opportunity to undertake systemic legal reforms, redefine the social contract between state and citizens, and reimagine governance rooted in justice and accountability. Yet, despite promises of reform, the agenda remains largely rhetorical and far removed from the aspirations of the people who risked everything for change.

This moment in Bangladesh’s history should not be wasted. The law must be reclaimed as a guardian of rights, not an enabler of oppression.